What is an opioid?

Opioids are natural, semi-synthetic, or synthetic chemicals that interact with opioid receptors in the body and brain and reduce perception of pain. While the terms opioids and opiates are sometimes used interchangeably, opiate refers specifically to natural compounds derived from the poppy plant, such as heroin or morphine, while opioids may be natural or derived in a lab.

Synthetic and semi-synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl and heroin respectively, are synthesized in a lab to mimic the effects of natural opiates such as morphine. They are developed to be stronger and more potent than natural opiates.

Prescription opioids are meant to be used to treat acute pain (such as recovering from injury or surgery), chronic pain, active-phase cancer treatment, palliative care and end-of-life care. Many people rely on prescription opioids to help manage their conditions under the care of a physician. Prescription pain relievers include oxycodone (OxyContin®) hydrocodone (Vicodin®), codeine, morphine, and others. Synthetic opioids include fentanyl, methadone, pethidine, tramadol and carfentanil.

Opioids reduce the perception of pain, and can also cause drowsiness, confusion, euphoria, nausea and constipation. At high doses they can slow breathing which can lead to death.

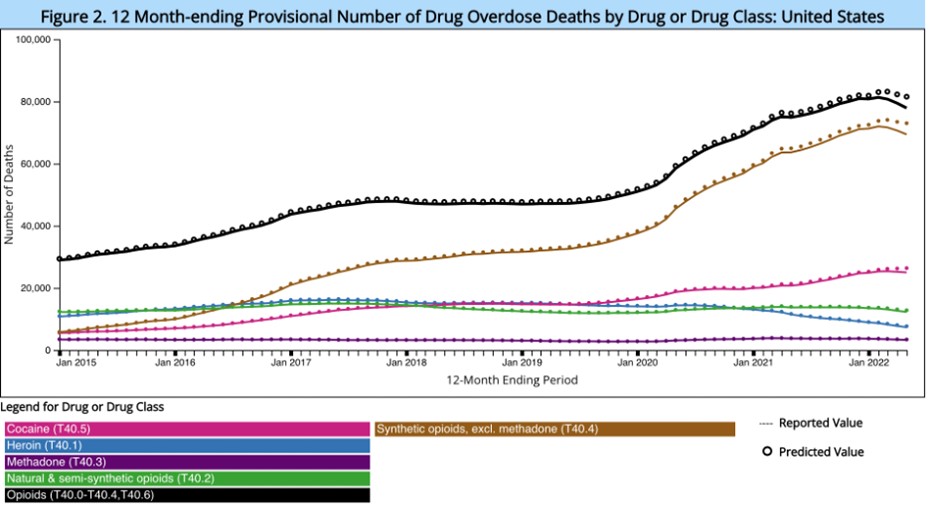

According to provisional data, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates more than 108,000 drug overdose deaths occurred in the 12-month period ending April 2022.1 While many types of drugs contribute to overdose mortality, opioids accounted for almost 75% of all drug overdoses deaths in 2020.2 The opioid crisis was declared a nationwide Public Health Emergency on Oct. 27, 2017. By June 2021, synthetic opioids were involved in an estimated 87% of opioid deaths and 65% of all drug overdose deaths.1

Figure 1: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2022.

Fentanyl

Fentanyl is 50 times more potent than heroin and 100 times more potent than morphine. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is prescribed to manage severe pain. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl is available in counterfeit pills or mixed with heroin and/or cocaine.3 In May of 2018, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) stated, "Fentanyl is the most prevalent and the most significant synthetic opioid threat to the United States."

Opioid Use Disorder Symptoms

Opioids produce feelings of euphoria which increase the odds that people will continue using them despite negative consequences. Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a chronic disorder, with serious potential consequences including disability, relapses and death. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM 5-TR) describes opioid use disorder as a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to problems or distress, with at least two of the following occurring within a 12-month period:

- Taking larger amounts or taking drugs over a longer period than intended.

- Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control opioid use.

- Spending a great deal of time obtaining or using the opioid or recovering from its effects.

- Craving, or a strong desire or urge to use opioids

- Problems fulfilling obligations at work, school or home.

- Continued opioid use despite having recurring social or interpersonal problems.

- Giving up or reducing activities because of opioid use.

- Using opioids in physically hazardous situations such as driving while under the influence of opiates.

- Continued opioid use despite ongoing physical or psychological problem likely to have been caused or worsened by opioids.

- Tolerance (i.e., need for increased amounts or diminished effect with continued use of the same amount)

- Experiencing withdrawal (opioid withdrawal syndrome) or taking opioids (or a closely related substance) to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms.

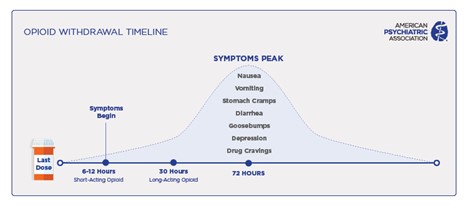

Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms

While opioid use disorder is similar to other substance use disorders in many respects, it has several unique features. Opioids can lead to physical dependence within a short time, as little as 4-8 weeks.3 In other words, the body will become used to opioids so that it has difficulty functioning without opioids. With chronic use, abruptly stopping use of opioids leads to withdrawal symptoms, including generalized pain, chills, cramps, diarrhea, dilated pupils, restlessness, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, insomnia, and very intense cravings. However, people do not die from opioid withdrawal. Because these symptoms are severe it creates significant motivation to continue using opioids to prevent withdrawal.

As with other substance use disorders, both genetic factors and environmental factors, such as exposure to trauma or ease of access, contribute to the risk of opioid use disorder.4 Access to prescription opioids and to heroin have contributed to the current opioid epidemic.

According to the American Medical Association (AMA), an estimated 3% to 19% of people who take prescription pain medications develop an addiction to them.5 People misusing opioids may try to switch from prescription pain killers to heroin when it is more easily available. About 45% of people who use heroin started with an addiction to prescription opioids, according to the AMA.

Treatment

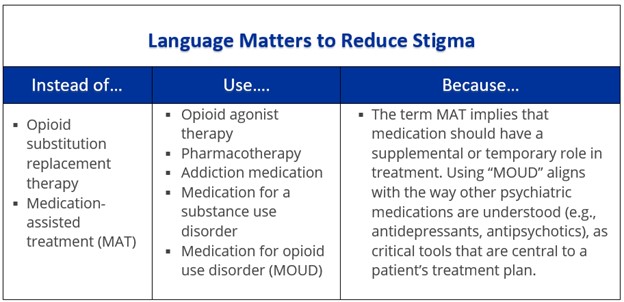

Effective treatments are available; however, only about one in four people with opioid use disorder receive specialty treatment. Considered the “gold-standard” of treatment, medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD), are an evidence-based treatment for individuals with an opioid use disorder.6 Counseling and behavioral therapies may be an important part of treatment alongside medications; however, they are effective by themselves.7 Medications are also used to relieve cravings, relieve withdrawal symptoms and block the euphoric effects of opioids. These medications do not “cure” the disorder, but rather improve safety and prevent withdrawal symptoms which can lead to relapse or continued drug use.

Three U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medications are commonly used to treat opioid use disorder:

- Methadone – Prevents withdrawal symptoms and reduces cravings in people with OUD. It does not cause a euphoric feeling once patients become tolerant to its effects. It is available only in specially regulated clinics.

- Buprenorphine (Subutex)– Partially blocks the effects of other opioids, displaces current opioids in the body, and reduces or eliminates withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Buprenorphine treatment (detoxification or maintenance) is provided by specially trained and qualified clinicians who have received a waiver from the DEA).

- Buprenorphine-Naloxone (Suboxone) - As stated above, buprenorphine partially blocks the effects of opioids. Suboxone combines buprenorphine with naloxone (see below) to prevent accidental or intentional use to get high.

- Buprenorphine extended-release (Sublocade) – a once-a-month injection of buprenorphine that is available to individuals that have shown tolerance to oral buprenorphine.

- Naltrexone – Blocks the effects of other opioids preventing the feeling of euphoria. It is available from office-based providers in pill form or monthly injection.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) emphasizes that these medications do not substitute one addiction for another. The dosage of medication used in treatment does not cause euphoria (a high)—it helps reduce opioid cravings and withdrawal. It helps restore balance to the brain circuits affected by addiction.

Treatment typically involves cognitive behavioral approaches, such as encouraging motivation to change and education about treatment and relapse prevention. It often includes participation in mutual-aid organizations, such as Narcotics Anonymous. MOUD have been shown to help people stay in treatment, and to reduce opioid use, opioid overdoses and risks associated with opioid use disorder, including HIV and HCV. 8

Different levels of treatment may be needed by different individuals or at different times, including outpatient counseling, intensive outpatient treatment, inpatient treatment, or long-term therapeutic communities. Opioid use disorder often requires continuing care to be effective. Evidence-based care for opioid use disorder involves several components, including:

- Personalized diagnosis and treatment planning tailored to the individual and family.

- Long-term management – Addiction is a chronic condition with the potential for both recovery and recurrence. Long-term outpatient care and support is important.

- Access to FDA-approved medications.

- Effective behavioral interventions delivered by trained professionals.

- Coordinated care for addiction and other conditions.

- Recovery support services, such as mutual aid groups, peer support specialists, and community services.

Table 1: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Words Matter - Terms to Use and Avoid When Talking About Addiction

Prevention and Public Health

Preventing overdose

Naloxone (Narcan, Evzio) is a life-saving medication used to quickly reverse an opioid overdose. It can reverse and block the effects of opioids and return normal breathing to someone whose breathing has slowed or stopped because of an opioid overdose. It is available as a prefilled auto-injection device, as a nasal spray and as an injectable. Naloxone is safe and has no effects if administered to someone not experiencing an opioid overdose.9

Naloxone administration will lead to rapid withdrawal from opioids. While it will improve breathing that has been slowed due to opioids, naloxone may also lead to vomiting which may increase the risk of choking. When administering naloxone, it is important to make sure the person being saved does not choke. Another important reminder is that naloxone works for a short amount of time. Therefore, a person may need multiple doses. If someone has been given naloxone due to a suspected overdose, they should be taken to the hospital after being given naloxone due to the risk of re-intoxication.

In April 2018, U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams, M.D., M.P.H., released a public health advisory to urge more Americans to carry naloxone. More information from NIDA on Naloxone can be found here.

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction refers to a set of evidence-based practices that can help reduce the potential negative consequences associated with substance use. It is a person-centered approach that can take many forms and helps keep individuals safer while also protecting public health. With opioid use, harm reduction might include participation in a syringe services program (SSP). Participation with an SSP is associated with lower rates of HIV and Hepatitis C and an increased likelihood of engaging in other forms of treatment as well as drug use cessation.10 SSPs offer many services including access to sterile syringes, collection of used syringes, and safer use training. Safer injection practices include techniques such as using a new sterile syringe for each injection, trying small doses of a new supply of a drug, and not using alone.

Additionally, SSPs often offer many other services such as counseling, case management, and naloxone distribution.

Avoiding opioids

If you or a family member is seeking treatment for acute or chronic pain seeking treatment, the AMA recommends talking with your physician about pain medications or treatments that are not opioids to avoid bringing opioids into your home.

Get more information from the CDC on non-opioid treatments for chronic pain and download a guide for managing pain for people in recovery(.pdf) from mental illness or substance use from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Resources

SAMHSA/HHS

- Rx Pain Medications KNOW THE OPTIONS • GET THE FACTS

- Treatments for Substance Use Disorders

- Finding Quality Treatment for Substance Use Disorders

- Treatment locator or 800-662-4358

- Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Spotlight on Opioids

National Institute on Drug Abuse

- Effective Treatments for Opioid Addiction

- Medications to Treat Opioid Use Disorder

- Prescription Pain Medications: Opioids Guide for Teens

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Opioid Overdose, Information for Patients

- Non Opioid Treatments for Chronic Pain

- Find Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder

Drug Enforcement Administration

American Society for Addiction Medicine

American Psychiatric Association

- The Opioid Crisis: Impact, Challenges, and Paths to Recover

- How to Help Those with Opioid Use Disorder in Jails & Prisons

- New Study Tests a Curriculum for Medical Students on Detecting and Treating Opioid Use Disorder

- Clinicians Resources Roundup: Opioid Use Disorder

- Nearly One in Three People Know Someone Addicted to Opioids; More than Half of Millennials believe it is Easy to Get Illegal Opioids

- American Psychiatric Association Renews Call to Action After Dramatic Increase in Overdose Deaths

- APA advocacy on opioid crisis

- Joint Principles on Opioid Crisis: Call for Comprehensive, Public Health Approach

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Statistics Rapid Release - Provisional Drug Overdose Data.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose: Death Rate Maps & Graphs.

- Sharma, B, et al. Opioid Use Disorders. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016 Jul; 25(3): 473–487.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4920977/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Polaris: Adverse Childhood Experiences.

- AMA Alliance. Prescription Opioid Epidemic: Know the Facts.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Facilitation of the Stepped Care Model and Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder.

- Carrol, K. M., & Weiss, R. D. The Role of Behavioral Interventions in Buprenorphine Maintenance Treatment: A Review. Am J Psychiatry 2016 Dec; 174(8): 738-747.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Naloxone DrugFacts.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syringe Services Programs Factsheet.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

- Figure 1: Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. National Center for Health Statistics. 2022.

- Table 1: National Institute on Drug Abuse. Words Matter - Terms to Use and Avoid When Talking About Addiction

Physician Review

Smita Das, M.D, Chair, APA Council on Addiction Psychiatry

Members of the Council's Opioid Task Force:

- Donald Egan, M.D.

- Benjamin Fraifeld, M.S.

- Brooke Trainum, J.D.

December 2022